Peripheral Retinal Hemorrhages a Literature Review and Report on Thirty-three Patients

- Instance study

- Open Access

- Published:

Retinal hemorrhages post-obit fingolimod treatment for multiple sclerosis; a case report

BMC Ophthalmology volume 15, Commodity number:135 (2015) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

Fingolimod is the beginning oral agent used for treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Macular edema, only not retinal hemorrhage, is a well-known adverse effect of fingolimod treatment. To the best of our noesis, this is the first example report of extensive retinal hemorrhages following fingolimod handling.

Example presentation

A 31-year-old male person with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis developed macular edema and retinal hemorrhages in his left center, 1 month after starting fingolimod treatment; treatment was and so discontinued. The hemorrhages were flame-shaped, and were extensive along retinal arteries and veins. The hemorrhages started to decrease at four weeks and disappeared completely at 24 weeks afterwards cessation of fingolimod treatment.

Conclusions

Occurrence of retinal hemorrhage warrants careful follow-up for multiple sclerosis patients treated with fingolimod.

Groundwork

Fingolimod (Gilenya®, Novartis, Emeryville, CA, USA) is the offset oral agent used for treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). Macular edema (ME) is a well-known agin effect of fingolimod treatment, occurring in approximately 0.iv % of patients [fingolimod-associated macular edema (FAME)] [one]. However, retinal hemorrhage has been nigh unrecognized as a side result of fingolimod treatment. We therefore report a case of extensive flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages in a patient treated with fingolimod.

Case presentation

A 31-year-old male with a thirteen-twelvemonth history of RRMS, after fingolimod treatment for one month, was diagnosed with ME and retinal hemorrhages in his left centre at a regular ophthalmic exam. His past history revealed that the onset of MS was accompanied by a visual disorder. He presented with several gadolinium-enhanced active lesions in his brain, despite therapies of steroid pulse, plasma exchanges, immunoglobulin, and interferon-beta (−β). Although interferon-β was used for a period of six months, 6 years prior, information technology was discontinued because of allergic skin reactions. The symptoms had improved after undergoing a course of five plasma exchanges 5 years prior but the patient refused further treatment. Over several years, the patient had adult paralysis in his right upper limb, both lower limbs, and had severe urinary incontinence and constipation. His Expanded Inability Score Calibration (EDSS) was 8.5. Anti-aquaporin-4 antibiotic tested negative. Laboratory studies, including haemorrhage and coagulation tests, were within normal limits. He had no history of hypertension (blood pressure approximately ninety–105/50–75 mmHg), diabetes mellitus, or hematological diseases. When retinal hemorrhages were recognized, the hemoglobin level was 15.0 g/dL and the platelet count was 210,000/μL (within the normal range). The patient had no history of uveitis and pars planitis.

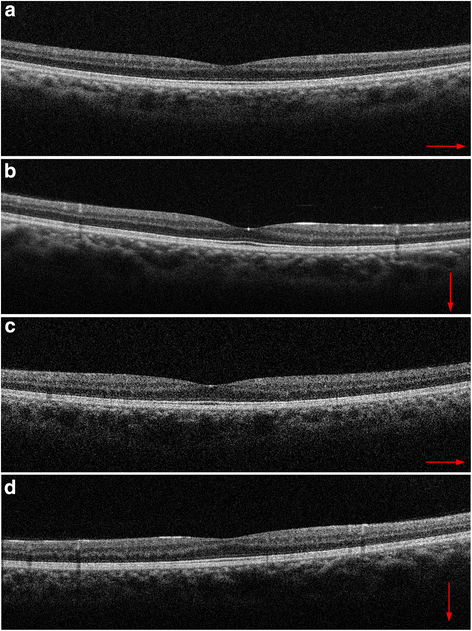

At the showtime ophthalmological examination before taking fingolimod, his corrected visual acuity was 20/600 OD and twenty/400 Os, optic disc color was pale, and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-Oct) showed a thinner retina (especially in the nerve cobweb layer) without ME in both optics (Fig. i). This was regarded as the cause of decreased visual acuity. In all directions, the patient showed gaze-evoked nystagmus.

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) scans of both optics before fingolimod treatment. The thinning of retinal nerve fiber layers was recognized, with (a) showing horizontal and (b) showing vertical images in the right eye, and (c) showing horizontal and (d) showing vertical images in the left center. Because of the patient'south nystagmus, the precise averaging of multiple SD-October B-scans was not possible, so single B-scan images are shown

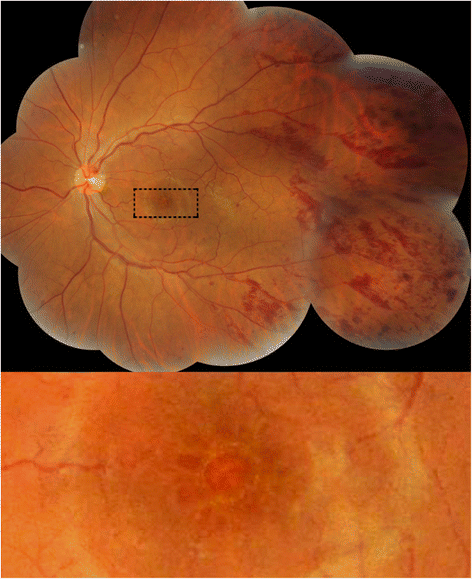

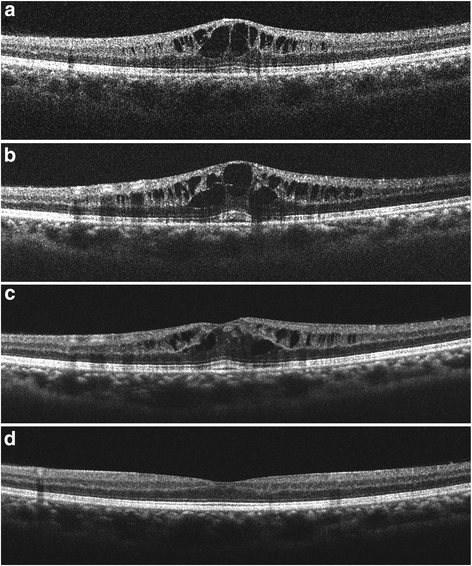

Iv weeks afterward fingolimod treatment, his left center revealed all-encompassing flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages along retinal arteries and veins (Fig. 2) likewise every bit cystic ME, as measured by SD-OCT (Fig. 3). His visual vigil did non decrease considerably, with xx/600 OD and 20/500 Bone. Most of the hemorrhages were found along both retinal arteries and veins beyond the mid-periphery involving all four quadrants of the retina. Deeper dot-blot hemorrhages, and a hemorrhage on the optic disc at the 12 to 1 o'clock position, were too recognized. The bore and tortuosity of the retinal veins afterwards the hemorrhages were the same as before the hemorrhages. Both optics had no inflammatory signs in the anterior segment and vitreous, equally assessed past slit lamp biomicroscopy test. Fingolimod was discontinued. Because FAME remained for 13 weeks, topical handling with 0.1 % betamethasone, four times daily, was started. FAME was resolved completely four weeks later starting topical steroid therapy; that was 17 weeks later the cessation of fingolimod. Retinal hemorrhages remained unchanged for iv weeks after the cessation of fingolimod treatment, and so started to decrease and disappeared completely at 24 weeks, indicating that the hemorrhages existed for seven weeks longer than the FAME. During the treatments and follow-ups, neither retinal hemorrhages nor ME developed in the right eye. The patient'south visual acuity at the fourth dimension of disappearance of retinal hemorrhages and FAME was 20/400 OD and xx/400 Bone. Fluorescein angiography was not performed considering the patient could not retain a sitting position.

Color fundus photography of the patient. Flame-shaped hemorrhages are seen forth the retinal arteries and veins in the left middle i calendar month later starting fingolimod treatment. Deeper dot-blot hemorrhages, and a hemorrhage on the disc at the 12 to 1 o'clock position, were also recognized. Moderate macular edema is as well shown

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) scans through the fovea. a 4 weeks after starting fingolimod handling, SD-OCT showed cystoid macular edema in the left centre. At that time, fingolimod was terminated. b Three weeks and (c) 13 weeks after cessation of fingolimod handling, macular edema was still present. Topical betamethasone treatment began at 13 weeks. d Macular edema resolved 4 weeks after topical steroid handling. Because of the patient'due south nystagmus, the precise averaging of multiple SDOCT B-scans was not possible, and single B-scan images are shown

Discussion

This case study revealed extensive flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages in addition to ME, post-obit fingolimod treatment. The retinal hemorrhages were mainly nowadays at the mid-periphery. There were no differences of retinal vein dilatation and tortuosity before and later hemorrhaging. The hemorrhage pattern was considered to be different from that of central or branch retinal vein occlusion. The patient had no history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or hematological diseases. Eales affliction and tuberculous vasculitis as well cause uni/bilateral peripheral retinal hemorrhages. Although the purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was not washed, the hemorrhages gradually disappeared completely in 24 weeks without oral corticosteroid or anti-tuberculosis handling after fingolimod was discontinued. There were no signs of vascular occlusion or retinal neovascularization that are oftentimes recognized in Eales disease.

To our cognition, there has been just one study of a macular hemorrhage without apparent causes following treatment with fingolimod [2] that was completely resolved presently afterward discontinuation of fingolimod. This example report suggests that fingolimod may play a role in disrupting vascular integrity, because hemorrhages are non routinely seen in MS patients without other signs of uveitis.

FAME is a well-known side effect of fingolimod. The sphingosine-one-phosphate (S1P) receptor plays a role in regulating vascular permeability, and enhancing endothelial barrier integrity. Fingolimod, a structural analog of S1P, inhibits this barrier action and leads to increased vascular permeability [three]. This may be the pathophysiological mechanism involving FAME.

Lightman et al. reported that cases of acute optic neuritis are characterized by retinal vascular abnormalities [four]. Their fluorescein angiograms showed multiple site leakage in the mid-peripheral retina. Optic neuritis patients with vascular abnormalities have a tendency to develop MS [4]. Recently, microcystic ME, predominantly affecting the inner nuclear layer, was reported in iv.7 % of patients with MS, and was more mutual in eyes with higher Multiple Sclerosis Severity Scores [5]. The presence of microcystic ME in MS suggests that there may be a breakup of the claret-retinal bulwark and tight junction integrity [5]. These observations propose that the mid-peripheral retinal hemorrhages described in the present case report may have been associated with MS-associated uveitis, and could have introduced blood retinal barrier disruption.

In the present case, nosotros found thinning of nervus cobweb layers at the aforementioned level in both eyes, but it was only in the left eye that ME and retinal hemorrhages were developed. In FAME, 74 % of onset is the single eye onset type [six]. In microcystic edema in MS, 2-thirds of the cases are reported as the single eye onset type [v]. The cause of symptom evolution in only a single eye is unclear, only MS patients are known to develop multiple and asymmetric symptoms.

Our case report suggests that not only multiple sclerosis inflammatory disease, merely besides MS handling with fingolimod, may lead to an increase in vascular permeability in some patients. Too FAME, in severe cases of MS with persistent inflammation, fingolimod may also crusade retinal hemorrhage.

Conclusions

Occurrence of retinal hemorrhages warrants conscientious follow-up of MS patients treated with fingolimod.

Consent

Because the patient could not motility his hands smoothly, written informed consent was obtained from the patient'southward mother for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this periodical.

Ethics approval

Approval for this piece of work was obtained from the Hakuaikai Ideals Commission of Kyoto, Nihon.

Abbreviations

- RRMS:

-

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

- ME:

-

Macular edema

- FAME:

-

Fingolimod-associated macular edema

- EDSS:

-

Expanded Inability Score Scale

- SD-Oct:

-

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- S1P:

-

Sphingosine-i-phospate

References

-

Melanie DW, David EJ, Myla DG. Overview and safety of fingolimod hydrochloride use in patients with multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:989–98.

-

Bhatti MT, Freedman SM, Mahmoud Thursday. Fingolimod therapy and macular hemorrhage. J Neuroophthalmol. 2013;33:370–2.

-

Jain N, Bhatti MT. Fingolimod-associated macular edema: incidence, detection and direction. Neurology. 2012;78:672–80.

-

Lightman S, McDonald WI, Bird Air-conditioning, Francis DA, Hoskins A, Batchelor JR, et al. Retinal venous sheathing in optic neuritis: its significance for the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1987;110:405–14.

-

Gelfand JM, Nolan R, Schwartz DM, Graves J, Light-green AJ. Microcystic macular oedema in multiple sclerosis is associated with disease severity. Brain. 2012;135:1786–93.

-

Zarbin MA, Jampol LM, Jager RD, Reder AT, Francis One thousand, Collins W, et al. Ophthalmic evaluations in clinical studies of fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1432–ix.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Takahiko Saida and Dr. Masami Paku for assistance in the writing of the manuscript. We did non have any funding for this piece of work.

Author information

Affiliations

Respective author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Both authors, NU and KS, had full access to the data, and read and canonical the last manuscript. Both authors were responsible for data collection. As the ophthalmologist, NU treated the patient, designed this report, drafted the manuscript and reviewed the literature. As the neurologist, KS as well treated the patient and participated in the design of the study, review of the literature, and review of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted utilise, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give advisable credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the information made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Ueda, Due north., Saida, K. Retinal hemorrhages following fingolimod treatment for multiple sclerosis; a case report. BMC Ophthalmol fifteen, 135 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-015-0125-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-015-0125-9

Keywords

- Retinal hemorrhages

- Fingolimod

- Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

- Side effect

- Macular edema

Source: https://bmcophthalmol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12886-015-0125-9

0 Response to "Peripheral Retinal Hemorrhages a Literature Review and Report on Thirty-three Patients"

Post a Comment